-

Business model generation

Business model generationAlexander Osterwalder & Yves Pigneur (2010)

A visual tool – with an iPad version for real-time modelling – that allows you to build up a visual representation of how a business operates. By focusing on nine key areas of any business, you can explore options for making changes. When combined with systems thinking (e.g. “Seeing the forest for the trees”) it is possible to conduct a deep analysis of the operation of a business, in a structured manner, and find ways to improve performance.

Roadmapping emergent technologies

Roadmapping emergent technologiesDavid Tolfree & Alan Smith (2009)

Many companies miss new business opportunities by not thinking about future technologies and products. Roadmapping is an established process that has been a valued tool of many successful companies. The authors of this book have captured their experience, and share it – with practical advice – with the reader who can then implement their own roadmapping programme (often part of a coherent innovation strategy).

-

Innovation choices

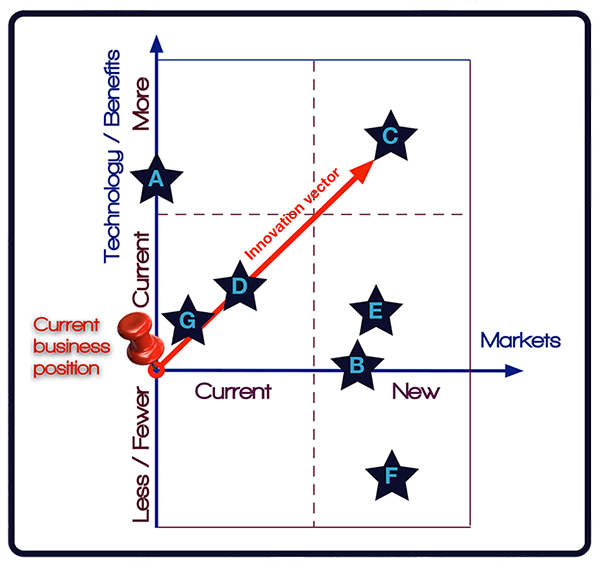

At a recent event on innovation, one of the questions that was asked was of participants was, “How much innovation does your business want?”

At first, I was puzzled, as I have never considered a quantum of innovation before. On reflection, however, I realised that such a question makes sense when one considers a vector of innovation – where innovation is a route to new markets and often requires new technology to deliver new benefits to customers.

The ‘Holy Grail’ of innovation might be considered to be ‘Disruptive Innovation’ where a new technology provides new benefits into new markets. However, sometimes an organisation finds it has some IP or unique technology and seeks to exploit it – through a ‘technology push’. Similarly, the market calls out for a product that a company cannot provide at present (market pull).

These, and other, innovation positions can be mapped into an innovation space, as illustrated.

These, and other, innovation positions can be mapped into an innovation space, as illustrated.The ‘technology push’ position (A) occurs when a review of the business identifies IP or a technology for which there is no obvious market application – as far as the business knows. There is a drive to find a market for the technology.

When a market is identified, but the business does not have a product to deliver the benefits required in the market, the business has to respond to this ‘market pull’ by trying to innovate and meet this market pull. This often reveals a gap between the market and the business’s current capabilities and products.

The ‘Holy Grail’ of innovation might be considered to be ‘disruptive innovation’ where a new technology brings new benefits into new markets. This also sets an ambitious innovation vector which is often very difficult to achieve for businesses that are efficiently organised for linear new product development processes (e.g. using Stage Gate models).

An innovation vector can have both magnitude and direction. A business can set its innovation strategy in the direction of ‘disruptive innovation’, but may define the strategy as being ‘the preferred supplier of technology solutions for our customers’ (D). This drives both the R&D and marketing sides of a business into achieving growth for the business, without major disruption to the business.

Another approach is to identify new markets into which the current business can move, without significant investment in new technology. This innovation vector (E) presents a range of challenges where barriers to market entry may not be clearly understood.

One of the biggest barriers to entering new markets might simply be cost and a product that is too sophisticated. Some markets can be entered with a lower level of technology, and fewer benefits, than current business provides (F). This innovation vector is counter-intuitive to many executives for whom innovation should be ‘upwards and forwards’. However, there are some compelling business benefits for adopting an innovation strategy with a vector that appears to be in the wrong direction, but which may, ultimately, open new markets and opportunities that had not been considered possible before (see ‘Reverse Innovation’ by Govindarajan and Trimble, for example).

One of the biggest barriers to entering new markets might simply be cost and a product that is too sophisticated. Some markets can be entered with a lower level of technology, and fewer benefits, than current business provides (F). This innovation vector is counter-intuitive to many executives for whom innovation should be ‘upwards and forwards’. However, there are some compelling business benefits for adopting an innovation strategy with a vector that appears to be in the wrong direction, but which may, ultimately, open new markets and opportunities that had not been considered possible before (see ‘Reverse Innovation’ by Govindarajan and Trimble, for example).Often, a business will recognise that it needs to ‘Innovate’ and initiates an innovation programme. Ideas are generated, potential markets identified, and ambitious goals are set. But, because of compromises that occur along the way, the ambition (and the innovation vector) are diminished and incremental innovation occurs (G) rather than the initial vision.

Each of these positions in the innovation space requires different strategies to either avoid or to achieve. Each position also has to be appropriate to the business. An effective innovation strategy has to consider the current business, what it is seeking to achieve (and what is realistic), and devise an approach to define the appropriate innovation vector and methodology. So, when you next are asked, “How much innovation does your business want?” remember that innovation does not come in quanta – it is a vector that has to be tailored to the business.

NOTE: Reference to the books in this article only means that Grounded Innovation values the insights within these books. The authors of these books are not associated with the comments in this article, nor do they necessarily endorse the conclusions expressed.