-

Ten Types of Innovation

Ten Types of InnovationLarry Keeley and others (2013)

Categorising innovation is rarely done, and leads to confusion and lack of focus. Keeley and his team have done a good job in capturing how the term ‘innovation’ can be applied across different areas of business, and how to make an effective impact. Keeley reminds the reader that innovation is more than just a brainstorm (usually just a collection of random ideas, sometimes also call a ‘thought shower’), and that focus and discipline are the keys to successful innovation.

Stranger than we can imagine

Stranger than we can imagineJohn Higgs (2015)

Higgs acknowledges the challenge that he set himself to tell the story of the 20th century from something other than a geo-political perspective. He ambitiously sets out with an agenda for a century that includes “relativity, cubism, the Somme, quantum mechanics, the id, existentialism, Stalin, psychedelics, chaos mathematics and climate change”, while acknowledging this is only a Western perspective on the century. Higgs sets out to look for “what was genuinely new, unexpected and radical” without using the term ‘innovation’. In the century when WB Yeats’ poem ‘The Second Coming’ observed "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”, this book goes some way to discuss how the new ideas of the 20th century brought us to the world of today.

-

Implementing innovation

While businesses recognise the need to innovate, it is not always clear how to do so in a way that is relevant and effective. There are many researchers who have explored the field of innovation, and some provide sound recommendations and strategies based on research. This white paper identifies three that are particularly relevant to those who engage in pragmatic innovation.

While businesses recognise the need to innovate, it is not always clear how to do so in a way that is relevant and effective. There are many researchers who have explored the field of innovation, and some provide sound recommendations and strategies based on research. This white paper identifies three that are particularly relevant to those who engage in pragmatic innovation.As a starting point, Govindarajan and Trimble (“The Other Side of Innovation”) make the point that many businesses have evolved to serve their markets efficiently and profitably.

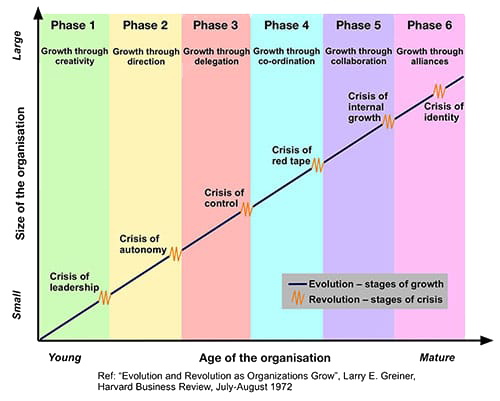

In doing so, businesses may have matured in ways that track the Greiner curve where the creative growth phase may have been overtaken by red tape (see illustration). This is not to say that the adoption of processes (or red tape) is a hindrance to a profitable business, but such processes can hinder radical innovation. Incremental innovation (e.g. using Cooper’s Stage Gate model) is a very effective tool when the objectives are clear, the resources are well-defined, and the management processes are coherent.

In doing so, businesses may have matured in ways that track the Greiner curve where the creative growth phase may have been overtaken by red tape (see illustration). This is not to say that the adoption of processes (or red tape) is a hindrance to a profitable business, but such processes can hinder radical innovation. Incremental innovation (e.g. using Cooper’s Stage Gate model) is a very effective tool when the objectives are clear, the resources are well-defined, and the management processes are coherent.If you have considered your innovation choices, and devised a strategy for radical innovation (or disruptive innovation), then you require something beyond incremental innovation.

Govindarajan and Trimble point out, however, that trying to implement an effective innovation strategy within a mature company can, unfortunately, be difficult and risks being ineffective.

Govindarajan and Trimble point out, however, that trying to implement an effective innovation strategy within a mature company can, unfortunately, be difficult and risks being ineffective.Griffin et al (“Serial Innovators”) explored this quandary and discovered that innovation can occur, and often does occur, despite red tape. While one approach can be to establish a ‘skunk works’ (as Lockheed Martin did), it is often down to determined individuals who can adapt the organisational resources in ways that help them innovate.

Dyer et al go further into exploring what makes certain individuals good entrepreneurial innovators (“The Innovator’s DNA”). Taking the research from Griffin and Dyer and their co-authors, one can distinguish the characteristics that can lead to effective, entrepreneurial innovation:

- Ensure there is scope for effective innovation by solving an identified problem:

- Is there the potential for significant financial impact if the problem can be solved?

- Is it likely that a solution can be found?

- Is the problem and its solution going to be acceptable to all stakeholders? Will it solve the problem and fit the strategy of the business?

The key lesson from both books is that innovation requires leadership and people, driven by innovation ambition and willing to tackle challenges to achieve this ambition.

The key lesson from both books is that innovation requires leadership and people, driven by innovation ambition and willing to tackle challenges to achieve this ambition.From the research results in these books, there are several different activities that emerge as necessary for an innovation strategy. These can be summarised as follows:

Curiosity. A key factor that drives successful innovation with serial innovators is curiosity and the desire to find an interesting problem. Griffin et al identified three criteria that are important for effective innovation:

- There is the potential for significant financial impact if the problem can be solved.

- A solution is feasible.

- The problem and its solution are acceptable to all stakeholders (it solves a problem and fits strategy).

Often this stage is categorised as the “Fuzzy Front End of Innovation”, but defining what this means is often ignored as it can appear a random process. The key activity is the search for an ‘interesting problem’. Dyer et al observed that effective innovators keep asking questions (e.g. the 5 Why’s). This curiosity and questioning is critical, and can seem “chaotic and non-linear”, but is done for a specific purpose. In a separate paper on Styles of Consultancy, this curiosity is a key aspect of the Fox’s nature.

Inspiration. Finding an ‘interesting problem’ is not trivial. It requires active engagement with all resources and some exploration – within the bounds of the company’s innovation strategy. Networking and asking questions are key activities done in this process. It also requires what is often termed ‘inspiration’ but which the researchers recognise to be a process involving questioning, observing and making associations across different disciplines and experiences. Again, this appears as a ‘non-linear’ and apparently ‘chaotic’ process – but, equally clearly, is being done with intent.

A core innovation team allows each member to share their ideas and knowledge with a view to stimulate a spark that might be the basis for an ‘interesting problem’. There are many innovative companies that adopt very similar strategies for significant commercial success.

Experiment. With an ‘interesting problem’ to tackle, the team would explore ways to solve this. Such experimenting work that is key to successful innovation and is often stimulated by a review of competences around the organisation (through informal networks as well as formal ones). This would be the basis for involving a range of relevant stakeholders in early discussions, workshops, and other collaborative work to identify the solution, validate it, and propose how to deliver the solution.

Networking. Networking is an essential part of an effective innovation activity. As John Donne observed (1624), “no man is an island entire of itself”. Networking is all about connecting people and often, in doing so, accessing new (i.e. unfamiliar) resources – both internal and external. It requires holistic thinking and cross-sectoral working, and an understanding of the agendas of different stakeholders.

Trust. Effective innovation requires a level of trust between parties. Inside large organisations, many informal networks exist, based on trust between individuals. Everybody involved in the innovation activity needs to be confident that everybody else is equally committed.

Exploitation. The route to exploitation of any solution will become clear during the engagement of stakeholders. This can only be achieved with an effective exploitation path – and engagement with appropriate partners who can achieve this. At this stage, the exploitation will lead to income.

Concern for the ‘greater good’. One of the key motivators for successful innovators is not financial reward; it is their own satisfaction in solving a problem that will benefit others significantly. This can pose challenges for management as the rewards for successful innovators comes as much from solving an “interesting problem” as from a bonus scheme with complex metrics. While an innovation strategy may define an innovation vector, the early stages may seem like a ‘random walk’ and can appear “chaotic and non-linear” in a mature company. They certainly do not follow the linear product development route that is appropriate for incremental innovation in large organisations.

However, as research shows, effective innovation requires a range of skills which do not need to be part of a business’s every-day skill set. Often, it is more effective to involve an outside organisation to initiate an innovation programme up to the point when the business can adopt the innovation output into its normal development work.

This is what Grounded Innovation offers to its clients: the skill set and experience to initiate effective innovation in a way that is compatible with the client’s business and strategy. Its approach and experience draws on the lessons from the three books mentioned in this white paper.

References:

- “The Other Side of Innovation” by Govindarajan and Trimble (published by Harvard Business School Press, 2010). The web site http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/chris.trimble/osi/ has further details of this book.

- Stage-Gate® process, developed by Dr Robert Cooper. See www.stage-gate.com

- “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow” by Larry Greiner (published by Harvard Business Review, 1972). A summary may be found on http://hbr.org/1998/05/evolution-and-revolution-as-organizations-grow/ar/1

- “Serial Innovators” by Griffin, Price, and Vojak (published by Stanford University Press, 2012). The web site www.abbiegriffin.org has a video trailer discussing the book.

- “The Innovator’s DNA” by Dyer, Gregersen, and Christensen (published by Harvard Business School Press in 2011). The web site www.innovatorsdna.com covers the principles described in the book.

NOTE: Reference to the books in this article only means that Grounded Innovation values the insights within these books. The authors of these books are not associated with the comments in this article, nor do they necessarily endorse the conclusions expressed.

- Ensure there is scope for effective innovation by solving an identified problem: